Global Horizons Showcases International Trade Insights in Collaboration with Leading Industry Bodies

The Association of Translation Companies is collaborating with the Chartered Institute of Export & International…

Elsa Huertas Barros and Juliet Vine, University of Westminster

New employees and new freelancers you work with will for the most part be the product of university courses in translation, usually master’s programmes. But what do these university courses offer their students? What do universities see as their main mission in providing training for translators and are they fully preparing graduates for employment in the real world?

These are some of the questions we have sought to answer in a survey carried out this year. The researchers received extensive data from over two thirds of all universities offering MAs in translation in the UK and Ireland. They used the data on the stated learning outcomes and the assessment practices of the MA programmes’ main language specific translation modules to reveal the priorities and the assumptions underlying these modules. This survey is a follow up survey on one carried out in 2016 and, as such, the results can also reveal trends within the courses.

Background information

This year we have been surveying UK and Irish universities who offer MAs in Translation / Translation and Interpreting. This is a follow up survey to the one we carried out in 2016. The focus of our survey has been assessment practices on the core translation modules. In 2016, we were particularly interested in exploring the perceived gap between what universities were teaching and assessing and what the language service providers felt needed to be addressed in training translators. In 2020 we wanted to see if there were changes in translation training programmes aims and objectives and how these are realised in the assessment patterns.

A total of 30 universities out of the 40 we contacted that offer MAs in Translation / Translation and Interpreting participated in the survey and we collected information on a total of 59 language specific practical translation modules offered on MA translation programmes with a focus on translation.

All university courses and individual modules on the courses need to provide a set of learning objectives (LO). As such, these LOs are a useful indicator of what universities think are important aspects of their training and, from the languages industry perspective, they can shed light on the issue of the gap between translation standards at university and those required by industry.

We analysed the LOs by comparing them to the European Masters in Translation competence framework (EMT, 2009). The EMT framework was devised by an expert group of academics from across Europe in conjunction with the European Commission’s DGT. The framework provides a list of competences which the expert group believed were necessary for a professional translator. By comparing the LOs on the core translation modules with the EMT framework, we wanted to assess to what extent MA programmes aims and objectives in training translators reflected those competences required of professional translators.

In order to make valid comparisons with our first survey results and to see, if and to what extent, the LOs have changed in the last 4 years, we used the EMT 2009, rather than the revised EMT competence framework (2017). The 2009 framework from an analysis point of view has the added benefit of clearly distinguishing between competences which are frequently found in the LOs, whereas the 2017 framework has amalgamated several competences to create a super ‘translation’ competence, which does not allow for more granular analysis.

The seven EMT 2009 competences can be summarised as follows:

Chart 1. EMT competence framework (EMT, 2009)

There were two approaches to creating a list of LOs. Most universities (25 of the 30 respondents) provided an undifferentiated list of on average 6 LOs per module which cover all forms of knowledge, skills and aptitude. The number of LOs is usually institutionally restricted, so these LOs are carefully chosen not to be exhaustive, but rather reflective of major aims. However, five of the 30 respondents did not follow this pattern and produced LOs which were divided into different dimensions such as: a) Knowledge and mastery and b) personal abilities. Another university gave categories which included key skills and practical professional skills. These five universities had a much larger number of LOs, averaging 19.1 per module and were thus able to cover a wider range of LOs. We term the first approach ‘simple LOs’ and the second ‘compound LOs’.

In the 2016 survey, the respondents gave standard simple LOs and so the simple LOs of 2020 were used as a comparison. The additional five universities will be discussed separately.

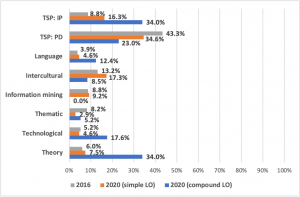

Chart 2. Breakdown of LO on language specific translation modules

The alignment of the LOs with the competences remains very similar in both surveys. This indicates that the universities have not significantly changed the objectives in terms of teaching the core translation skills. This is particularly surprising in terms of the technological competence. Even though many MA courses provide a separate specialist CAT tools module, we would have expected more universities to be embedding CAT and other technological skills in the main translation modules.

The Translation Service Provision (TSP) remains the overwhelming most common LO of core translation modules, accounting for 50.9% of all simple LOs in the 2020 survey compared to 52.1% in 2016. Given that TSP is the key translation competence in the framework (one that is interrelated to all the other competences), this finding is not surprising, but rather confirms that the modules all have a similar focus on this key competence.

However, when the TSP is divided into its two component parts, there is a shift in focus from the TSP Product dimension (PD) to TSP Interpersonal and Personal dimension (IP) in the findings of the two surveys. This indicates that universities are widening the scope of the learning objectives to include a greater emphasis professional practice and ethics, as well as the transferrable skills related to any profession such as working to deadlines and negotiating with clients.

In the recent survey, when the compound LOs are analysed i.e. the longer list of LOs differentiated into several dimensions, the TSP competence is also found to be the most prominent category of LOs. However, whereas the simple LOs were divided in TSP IP (16.3%) and TSP PD (34.6%), the compound LOs were divided TSP IP (34%) and TSP PD (23%). When universities were not constrained in the number of LOs and when the LOs express a wider range of dimensions, it is interesting that translator professionalism and transferrable skills such as teamwork and project management become much more prominent as LOs.

In both the 2016 and 2020 surveys, after TSP competence, the next most commonly expressed LO relates to the translator’s role as an intercultural mediator and in particular being able to identify and respond to differences in the sociolinguistic conventions of the two language-using communities. Not only was the intercultural competence prominent in the number of times it was mentioned (2016 -> 13.2% of LOs and 2020 -> 17.2%), but this competence occurred as the first LO to be mentioned in 29% of the modules which gave simple LOs. This was nearly equivalent of the simple LOs mentioning TSP first in their list (35%).

Main findings on assessment instruments and tasks

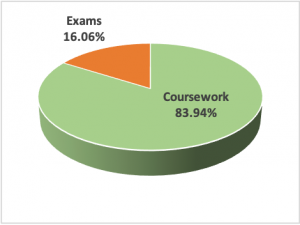

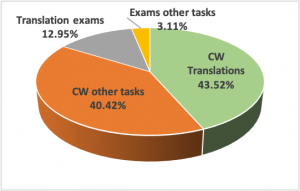

Chart 1 and 2. Type of assessment instruments used on language specific translation modules (academic year 2019/2020)

Types of assessment tasks

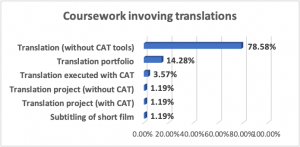

Chart 3. Breakdown of coursework involving translations

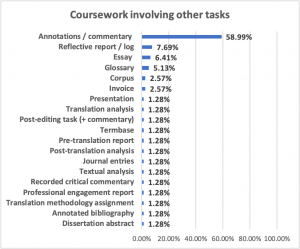

Chart 4. Breakdown of coursework involving other tasks

Word count & time frame allocated to translations

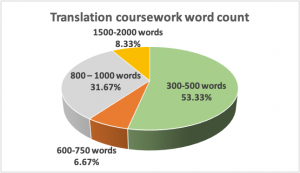

Chart 5. Breakdown of translation coursework word count

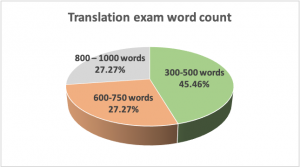

Chart 6. Breakdown of translation exam word count